A Label For Pressing Sustainability And Social Issues

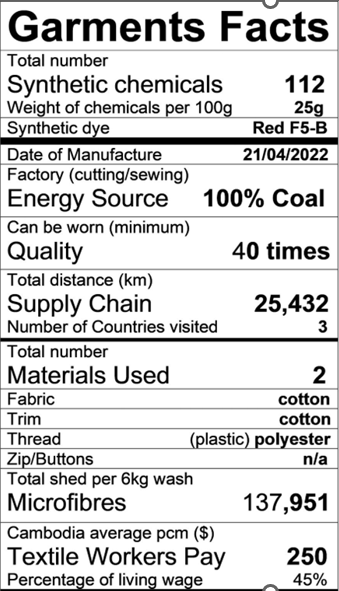

A proposed “fashion nutrition label”

© Peter Gorse

On November 6th UCRF held its first event of Action Season Two, this time with a point of departure of a suggestion for a new apparel label from one of our members.

Peter Gorse, who is an industrial designer, has developed an idea for a new approach to labelling apparel based on how food is labelled and UCRF opened up for a discussion on this. Since its inception, Gorse’s Garment Facts label has enjoyed a fair deal of attention on social media, recently written about in Vogue Business and most recently — nominated for the Global Change Awards for 2025.

Context and Legislative Backdrop

As a backdrop, it is important to note that Peter Gorse and UCRF board-member Tone S. Tobiasson had recently attended a validation workshop facilitated by the European Commission on the Textile Labelling Regulation for the physical labels on apparel, in order to explore the European Union’s willingness (and the industry’s readiness) to expand the information available on these.

The session’s outcome suggested that there is not much leverage in this space; the wish is to effectively shrink the information on the physical labels and “push” any “sustainability and circularity” related information to the Digital Product Passport (DPP), which will be mandated under the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR).

For the physical labels, they must include care instructions (as today, icon-based), fiber content (with more accuracy for recycling purposes, and a wish for these too to become icons). “Made in” is only mandatory in some countries. However, after the Commission’s validation workshop, both Peter and Tone sent in comments asking for inclusion of more objective “metrics”, in line with what is mandated in other markets. This could include, for example, date of production or entry to market, or data related to microfibers or microplastics.

While we do not yet know the results of this discussion on the Textile Labelling Regulation, we do know others in the workshop have also been advocating for this (e.g., ECOS, Fairtrade and EEB).

In the meantime, as the “sustainability and circularity” information is being moved on to the DPP under ESPR, this is a chance to reinvigorate the Policy & Social Change group’s work to ensure that information included therein is not subjective (e.g., based on PEF and weighting of highly disputed data), but rather objective data and knowledge (also social issues), and here is where Peter’s label presents an alternative approach.

From the Labelling event on 6th November

The UCRF Labelling Event Workshop

This is what the participants spent a good hour and a half discussing on November 6th, by addressing each element of the proposed label in terms of their feasibility and importance. The seven members who attended the session had very different perspectives, but also agreed on many aspects. Each member was asked to evaluate their perceived feasibility (i.e., how realistic is it to measure a specific metric, based on their experience) and importance (i.e., how critical is it to include such information for consumers) of the label’s eight components, on a five-point Likert scale. In addition, each member added comments under each of the elements, raising questions that were later discussed.

The elements, or metrics, that received the highest ‘ranking’ from the participants, were: “Supply Chain Distance” (distance traveled in kilometers), “Number of Materials Used” and “Synthetic Chemicals”.

For ‘synthetical chemicals’ though, the comments brought forward that the consumer may or may not understand what this actually means. ‘Chemicals’ as a metric is one thing: water is a chemical, and chemicals in themselves are not inherently ‘bad’. On top of that, do consumers understand that almost all our clothes are synthetically dyed, and treated with a myriad of synthetic treatments that we rely on? For wind- and waterproofness, for non-flammability, non-shrinking, etc. (NB: news that another flame-retardant has been ruled as substance of concern was just released, after 12 years of testing). That one synthetic dye is highlighted on the label, was questioned here, highlighting that a technical-sounding name can in fact add confusion and obstruct consumer awareness. Peter’s idea was that including the number of synthetic chemicals enhances understanding and is thus an eye-opener in and of itself. However, the question of consumer comprehension must be seriously considered, and our discussion suggests the need for broader efforts in raising consumer awareness around the chemical treatment of textiles.

Supply-chain distance is easy to grasp, but perhaps harder for SMEs to obtain reliable transparency metrics on, depending on their textile sourcing strategy, digital traceability capabilities and supplier readiness. However, some see this as a “Fibershed” eye-opener! Could all the countries actually be listed, was one pertinent question. Such a metric could be a powerful signal to consumers regarding a retailer’s sourcing, manufacture and distribution strategies—ultimately incentivising consumers to support brands prioritising short-distance business models.

Number of materials is important for recycling purposes, yes. The fiber content has to be on the label; however, it turns out that there are discrepancies. Will the number of materials help to avoid confusion here? A suggestion to include the amount of fabric used per item (in metres or grams) was brought up as a potential indicator of wastage during assembly. Another proposal pertained to the indication of labelling synthetic materials derived from fossil-fuels as “Plastic”, as not all consumers will understand what e.g. “Spandex” or “Nylon” means in terms of its actual chemical composition, but whose purchasing decision may be impacted should they more clearly associate such textiles as “containing plastics”. This echoed the earlier discussion around Synthetic Chemicals and the ability of consumers to derive useful understanding from such distinctions. Others suggested that while listing the composition of different components should be relatively easy—as it is frequently required for costing calculations—there still remain challenges for brands who rely on second-tier suppliers to source trimmings and finishings, further fragmenting and obscuring the value chain.

There were several other points discussed, for example if times projected for use is synonymous with quality? On the one hand we have “intrinsic durability” (can be measured with physical durability by conventional resistance testing, colorfastness, etc.) and then there is “extrinsic durability” (sometimes dubbed “emotional durability”) pertaining to other perceived values—in essence, how long do we keep and use our garments? What is the Duration of Service (DoS)? Further discussions on social metrics such as percentage of living wage paid to assembly workers as being critical but challenging metrics to obtain and publicise for retailers, further highlighted the tensions between feasibility and criticality, and the capabilities disparity between large players and SMEs.

An excerpt from the workshop output

Where does this take us?

The main concern here is that we need – really need – label info or metrics, that is objective. If ESPR is going to include PEF, we risk highly subjective data entering a data-stream towards the consumer, that will not make sense.

We therefore would like to open up this discussion beyond the small and engaged group that attended the workshop. One way to contribute as individuals is by registering as a stakeholder with the European Commission and Joint Research Centre’s study on textile products. This will get you invited to consultation sessions where you directly campaign for the inclusion of objective metrics. There are dedicated pages as well for ESPR and DPP where one could follow and contribute to policy consultations on these topics.

Another way is to engage in conversations online—from LinkedIn to YouTube and TikTok, bringing the topic of garment and textile labelling forward is a crucial part of awareness-building. We suggest following Peter Gorse on LinkedIn, and looking at what organisations such as ECOS, Circle Economy and engage with communicators who strive to provide accurate and accessible information to consumers.

If you have suggestions for additional stakeholders or events where this dialogue could continue, please share your ideas with us. Your voice is critical to advancing this initiative.

We need to remain pragmatic and outcome-focused, without compromising information quality. After all, consumers will only trust data that is reliable and easy to comprehend, and we must respect their attention, and strike the balance between meeting them where they are, and stimulating them to learn more about their choices.

We hope that together we can continue to drive meaningful discussion on how to empower consumers to make informed decisions, and stimulate the industry’s accountability by engaging with policymakers on what needs to be done to do so.

Guided by our Manifesto, UCRF is committed to amplifying diverse voices and perspectives. Our goal is to foster an activist knowledge ecology and lead critical debates on fashion's systemic challenges. While we do not endorse a single viewpoint, we seek to offer a platform for varied ideas that inspire further dialogue and inquiry.